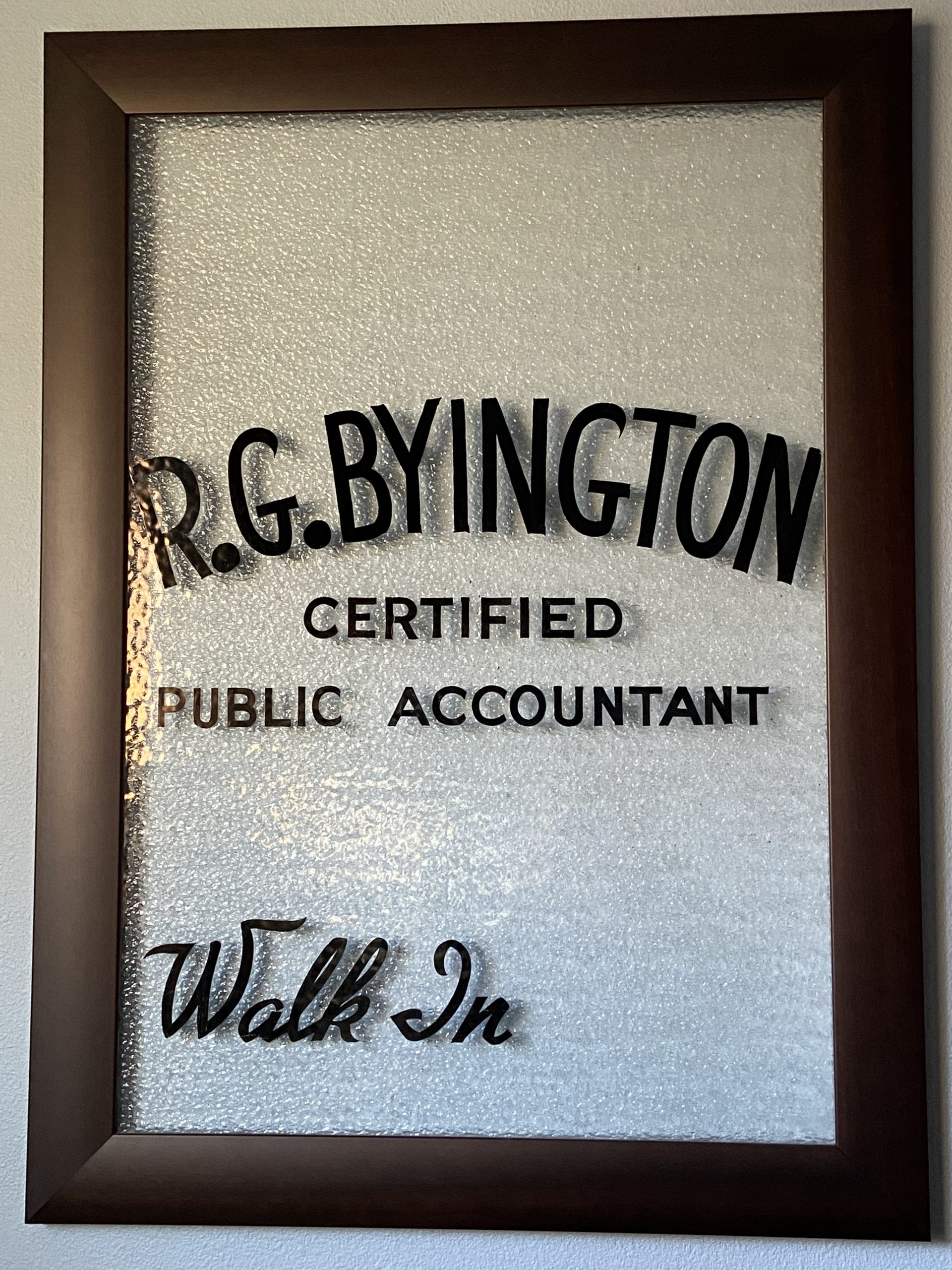

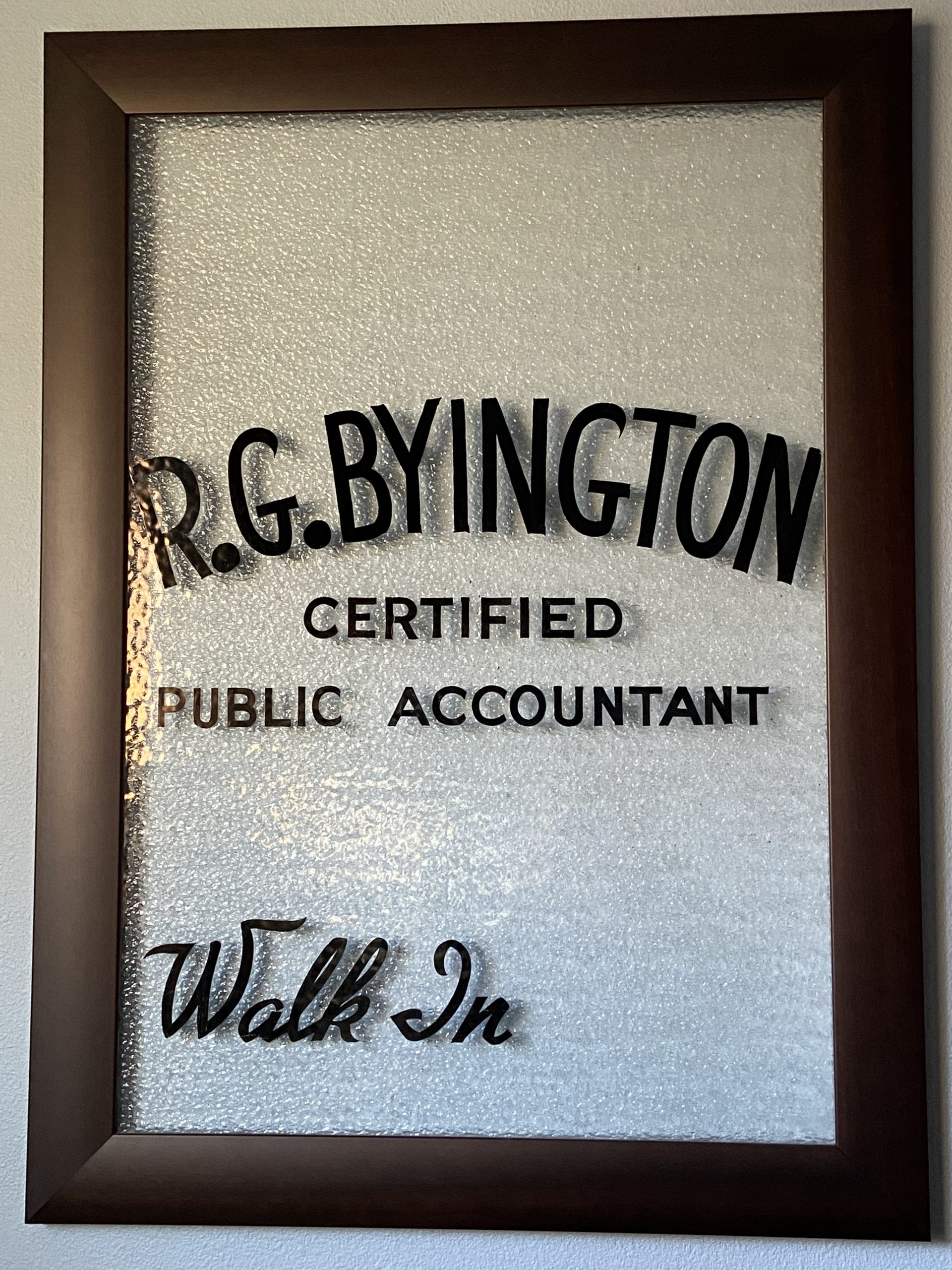

This is the window to my father’s CPA office. My sister Bobbi rescued it from the basement of the Daly Bank Building in Anaconda a few years ago. She and her husband Mike brought it out west, and I had it framed. It hangs on the wall of my home office. Some of you may even remember it. I stare at it often and think back to the days when I would head up the stairs of the building, the smell of dust in the air. My sister and I would push each other around the second floor in office chairs.

This is the window to my father’s CPA office. My sister Bobbi rescued it from the basement of the Daly Bank Building in Anaconda a few years ago. She and her husband Mike brought it out west, and I had it framed. It hangs on the wall of my home office. Some of you may even remember it. I stare at it often and think back to the days when I would head up the stairs of the building, the smell of dust in the air. My sister and I would push each other around the second floor in office chairs.

That came to a full stop when I accidentally pushed her, chair and all, down the steps.

Anyway. Today, when the sun caught the corner of it, I thought back to this day 34 years ago. And I thought I’d share this chapter of Smelter City Boy.

This is the third in a triptych of stories loosely collected around cars and the times I’ve spent in several cars with my dad.

My dear old dad.

_____________

1962 Ford Falcon

March 1987

Dad regarded the new bag of plasma hanging beside his bed. The day nurse hooked the bag into the shunt on his forearm. She started the drip, looked at her wristwatch and entered the time in the chart.

“Yum,” he said.

“Yeah, well. Let’s try to keep this blood inside your veins this time,” the nurse said before leaving.

The night before, he had scratched his shin and nearly bled to death. It sounded like it was a hell of a mess when Mom called and told me I’d better come for a visit. I’d been working around the clock on opening a show I was co-choreographing, so I hadn’t come to see him in quite a while. The latest round of radiation had caused him to hallucinate, so he landed in the hospital about a week before. I felt he was on hospice care, but no one would actually confirm that was the case.

“I scratched myself and nearly killed myself,” Dad said.

“How’d you manage to do that?” I asked. My father hadn’t had any feeling in his lower legs since his first few rounds of radiation. His war injuries were the first places to show weakness, then deterioration, then cancer.

“Killer toenails!” Dad said and pulled the covers off his feet.

It wasn’t a pretty sight. His feet were swollen almost to the point of looking bruised. The nails were atrocious. They looked like they hadn’t been cut in years.

“Pop! What the hell?” I asked.

“I can’t reach, and I know better than to ask strangers to do this,” he said.

“I don’t know what that means,” I said.

“Nevermind, Big G,” he said, glancing at the plasma. I pushed the call button. “Let’s see what we can do about that,” I said.

He had taken to dividing his free time between watching the Home Shopping Network and the Christian Broadcasting Network. Both channels made him angry enough to provide plenty of conversation starters. Today he was studying Pat Robertson.

“Look at that jackass. Have you ever listened closely to what that man is saying?” he asked.

“Not really,” I said. “I don’t let those guys get the better of me.”

“Well, he’s absolutely parasitic! He takes advantage of people when they are really down and out, you know? He’s always asking if people are lonely or in a bad way. Then he spouts some crap about God loving them no matter how desperate they are. Then he hits them up for cash.”

“You know my friends Rob and John? They subscribe to the 700 Club under the assumed name of Percy Manlove. You should see the propaganda they send out,” I said.

“Rob and John are—”

“Gay,” I said.

“Right,” Dad said.

When the nurse showed up at the door, I asked her to bring me a toenail clipper. She opened the drawer in the nightstand and pulled one out, dropping it in my hand. “Huh, what do you know,” Dad said. “There was one there all the time.”

I sat on the foot of the bed and took up my father’s swollen right foot. Cool to the touch, the skin was pulled so tight it looked like it would burst if I accidentally nipped it with the clippers.

“Your toes are a mess,” I said.

“Yeah, well. I don’t get around much anymore,” Dad said.

Three toes in, he was sound asleep, and my mind was wandering.

###

It was the summer of 1984 when Dad told me he was sick. I was in Artesia, New Mexico, touring with MCT. It was a Sunday; I always called home on Sunday. I had been watching Dr. Zhivago on the small television in my motel room. Every room I ever stayed in drifted in and out of my mind. I was looking at Julie Christie when my father said, “I’ve got some news.”

The rest of the conversation faded in and out of memory as I carefully clipped each toenail. I remembered telling him it wasn’t all that bad. That prostate cancer wasn’t a killer, as far as I knew. And I remember him being optimistic, too.

There’s a montage in Dr. Zhivago where he spends the winter with his mistress in an abandoned house. I thought how cold it must have been in Russia during the revolution. The place looked like it was grand at one time but had faded into obscurity. A child was running through the halls. A little girl, I thought—the doctor’s love child.

When I started to clip the other foot, I recalled how Dad insisted I talk to the oncologist all by myself. I’d taken him to Missoula to see his specialists, and he walked into the waiting room and told me the doctor wanted to speak with me.

“Your father is going to die,” the doctor said, “of prostate cancer.” He went on to tell me how all men, even if they were reasonably healthy, would sooner or later have a brush with prostate cancer.

“The only thing we can do is make him comfortable with radiation,” the doctor said. “We’re going to remove his testicles to try to stop the spread of the cancerous cells, but that’s really just a stop-gap measure. We’ll do some radiation, but he has requested no chemotherapy.”

“Did he say that?” I asked. “I mean, did he actually say those words?”

“He said, ‘No heroics,’ and he told me about your relative, his sister, I think?”

“Lola, yes. Breast cancer,” I said.

“Right. Well, apparently, she did all sorts of things to stay alive. Including some kind of trip to Mexico?”

“I don’t recall if they actually made that trip. But I remember her eating so many carrots she turned orange,” I said.

“Your father doesn’t want any of that, and he wanted me to tell you not to insist on anything beyond just comfort care,” he said. “And if I were you, I’d get a prostate exam once a year,” he said. “We’re going to start recommending people get a yearly exam when they are fifty, but you are high risk now.”

I was twenty-three.

“I want you to see something,” the doctor said. And he flipped on a lightbox with a series of x-rays clipped to the front. “These are x-rays of your father’s bone structure,” he said. “Every bright spot is a place that has been broken. Your dad was in an accident some time ago.”

“Yes, Jeep accident in the war. He broke his femur,” I said.

“He broke a lot more than that,” he said. “These weak areas are where cancer, should it metastasize, is likely to spread.”

I looked at the x-rays. There was a constellation of bright spots on Dad’s bones.

###

The late afternoon sun was starting to climb its way across the floor. The plasma bag was long gone. The toenails were clipped short, and the feet tucked safely away under an extra blanket. While some woman blathered on about luxurious cotton robes—a Home Shopping Network exclusive—I sat next to my sleeping father and worked one of his empty crossword puzzles. Lulled by the gentle rise and fall of his breathing, I hardly stirred when he said, “Where’d you get those?”

“From the nightstand,” I said. He was sound asleep.

“These cherries. Where’d they come from?” he asked.

“What?” I asked.

“This bag of cherries,” he said, plain as day. I checked once more. His eyes were closed, and he was clearly asleep.

“I don’t know,” I said.

No one had prepared me for this. I didn’t know whether to wake him or indulge him.

Either way, my heart started pumping extra fast. My mind raced to the night a few years before when I was student teaching. I was jerked awake to the sound of his bedroom door banging against the wall.

“Good. Damn good! Must be late-crop Bings,” he said.

“Yeah,” I said. “Probably.”

I watched as he picked a cherry from an imaginary bag he had balanced on his chest. Slowly pulling the stem up, flipping the cherry into his mouth, pulling the stem out and spitting the pit across the room. Had we not been in a hospital room with visiting hours drawing to a close, I would have thought we were laying in a hammock somewhere on the shores of Flathead Lake.

That night. Was it two years ago? Three now? They had a tendency to melt into one another. He had called out to me. He’d fallen. Frozen with fear, I recalled how he called my name. He broke his back that night and had to walk with a cane after that.

“It’s the damn column shift,” he said, spitting. I was jerked back into the hospital room. “Confuses people, I think.”

“What do you mean?”

“Well, you know. The Falcon. The shift is on the steering column, and people just get perplexed.”

“Yeah?”

“Well, hell yes! Should have gotten the automatic … what’s-it-called … Ford-O-Matic transmission. But seeing as how I was the only one driving, I just didn’t see the point. We’re never going to sell that car,” he said.

I hadn’t thought about the Falcon station wagon for years. Dad bought it shortly before I was born. It used to sit in the field on the other side of the street before the Lussys built their house. Then I think Dad moved it into his storage garage with a bunch of stuff from his bachelor days. We used to drive it to the dump whenever we had a load big enough to fill the back.

“How much have we got there?” he asked.

“What?”

“On the meter. How much?” He was starting to get irritated.

“Oh! Uh … three and a quarter?” I said, not entirely sure I should be making stuff up.

“Well, slip out and pay the man, will you? My leg is killing me today,” he said. A split second later, he added, “You’re taking too long with my money.”

Stunned, I turned and looked beyond his feet out the window at the foot of his bed. He was smirking when he drifted deeper into sleep.

###

I stood up and stretched. Paced a little bit. The day was escaping from me, and I had to be back in Missoula that night. We had just moved out of the rehearsal hall and into the theatre. There was a lot to do. I sat back down by the side of the bed and considered slipping away. Once everything quieted down, I remembered the day he taught me how to mow the lawn.

We didn’t have much of a yard, so he insisted on a small, electric lawnmower. Of course, I wanted a big gasoline-powered mower with a bag to catch the clippings. Instead, he said if we mowed with the tiny, blue electric mower at least once a week, we wouldn’t have to bag any of the clippings. He made me walk alongside him, next to the mower.

I was impatient. He was steady and slow.

I had gotten just a bit ahead of him, nearer to the mower than I should have been, when he ran over a pork chop bone left in the lawn by Honey Yvette. I heard the bone run through the blades about the same time I felt two pokes in my face like I’d been shot with a b.b. gun. One shard lodged in my brow, just between my eyes. The other totally cut through my upper lip.

“Good God!” He shouted. “I’m sorry, but you need to listen to me and do what I tell you at least once in a while. I know you don’t think so, but I do know what I’m doing,” he said.

It was the only apology he ever gave me.

The second announcement for the close of visiting hours had just finished when he woke up. His eyes darted around the room. For a second, I thought he looked like a scared child, unsure where he was or what was going on. Finally, he coughed a bit, yawned and looked at me.

“What are you up to?” he asked.

“Not much. I was just doing a crossword and watching the fabulous exclusive values I can order, using a toll-free number,” I said.

“Never thought I’d see the day when people would be buying diamonds from the television,” he said. “Then again, never thought I’d see the day when a scratch could make you bleed like a stuck pig.”

“Well, your nails are clipped,” I said. “You should ask the nurse to file them down for you .”

“Wouldn’t do any good,” he said. His eyes drifted around the room, away from me.

Then he stared at his feet, propped up under the covers and said, “I’m rotting from the inside out.”

“Well, that’s reassuring,” I said.

“What are you doing here?” he asked.

“I came to see you,” I said.

“No. I mean it. What are you really doing here?” he asked again. I tilted my head a little and puffed out my cheeks. Then my mouth just sort of hung open for a second. “What’s the show about?”

“What?” I asked.

“The show? What’s it about?” he said.

“Oh! Well, it’s about a whorehouse.”

“You don’t dance in a whorehouse,” he said.

“You do when it’s the Best Little Whorehouse in Texas,” I said.

“Oh! That one,” he said. “I saw the movie on VHS.”

“The play is better.”

“Lots of dancing cowboys and whores in that one,” he said.

“Well, they are football players dressed like cowboys and whores dressed like prom queens, but—yeah—I’ve got my hands full,” I said.

The sun had traveled to the other side of the hospital. The room was full of shadows, so I opened the blinds and turned on the reading light above the bed.

“You better get to it, then,” he said, smoothing the sheets on either side of his hips.

“Dad, I’m afraid I won’t. I mean, I can’t. I mean … I don’t know what I mean,” I said finally.

After a while, he said, “Listen, I think you have better things to do than come here and watch me sleep.”

“I can’t think of anything better right now,” I said.

“You lie like a rug, Big G.”

I stood up slowly and put the book of crossword puzzles back on the nightstand. Not knowing what else to do, I leaned over and gently kissed his forehead.

“I’ll see you later,” I said at the door.

“Drive safely,” he said.

And that was it.

Later that night, I was leading the cast through a series of warm-up stretches on the Wilma stage back in Missoula when the phone on the Stage Manager’s station rang. It was B.J. Dad had fallen asleep after I’d left and didn’t wake up when the nurse tried to rouse him for dinner.